[ad_1]

One suggestion by the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, which is pushing for electoral reforms in the country, is to do away with the traditional system of counting paper ballots and replace it with Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs), where a voter can punch in their vote electronically.

Earlier this year, the government also unveiled a prototype of an EVM machine it aims to roll out for the 2023 national polls. But exactly how feasible is this option, really? Can Pakistan afford it? And, more importantly, will it work in ensuring free and fair elections?

In a recent seminar organised by Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT), titled “Demystifying Electoral Reforms in Pakistan”, Atif Majeed, a digital product development specialist, answered some of these questions.

Interestingly, Majeed was part of the team that created the first EVM in Pakistan, back in 2011. His model, he told the seminar, has now been dusted and reproduced by the government 10 years later.

To get a sense of the scale of what a switch from traditional voting to electronic voting entails, Geo.tv followed up with Majeed regarding some of the key challenges seen in implementing the process.

What follows are the key numbers behind Pakistan’s electoral process, and the challenges they might bring.

How many EVMs does Pakistan need?

It should be pointed out here that an electronic voting system does not just comprise a single machine in a polling booth. Instead, the system utilises multiple ‘modules’ that work together to enable the electronic voting process.

Majeed explains that a complete EVM solution comprises the following modules:

- A Voter Identification Unit

- A Control Unit

- A Balloting Unit

- Printer-based Paper Audit Trail Box (Printer Box), and

- RTS Module

Now, lets get a scale of how large the traditional voting exercise is.

In the 2018 polls, Pakistan had:

- 85,000 polling stations,

- 240,000 polling booths, and

- 95,000 voter identification units.

Going by the number of polling stations, polling booths and voter identification units used in the 2018 polls, Pakistan will need a total of 900,000-1,000,000 of these five different EVM modules to conduct polls for all provincial and national assembly seats in a single day, which is a requirement set out in the law.

Individually, how many of each module will Pakistan need?

Approximately:

- 100,000 Voter Identification Units

- 200,000 Control Units

- 400,000 Ballot Units

- 100,000 Printers

- 100,000 RTS Modules

What would the total cost for all these modules come out to be?

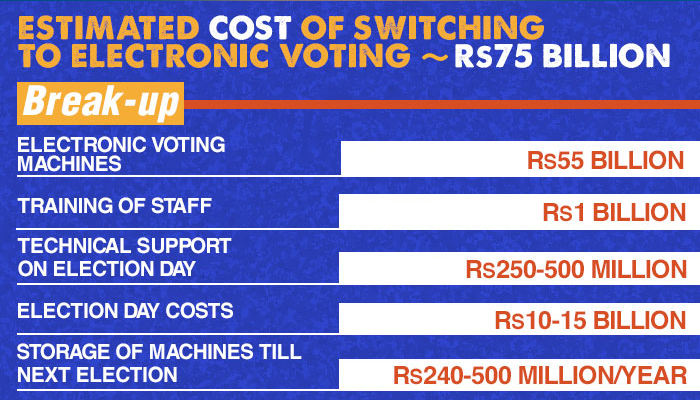

The total cost for 900,000 to one million modules will come to Rs45 billion to Rs70 billion, estimates Majeed.

“The printer is the most expensive module. Any good printer is going to cost $700-1,000 each. The total for the printers will ring up to about Rs15bn in local currency,” Majeed explained.

“Meanwhile, Voter Identification Modules will cost around Rs10bn, while a reasonable quality Control Unit will cost $500 each (so about Rs15bn in total). Likewise, a reasonable quality Ballot Unit will cost $200 each, so about Rs12 billion. RTS Modules will cost a further Rs2-3bn,” Majeed added.

“The total bill for this amounts to Rs55bn. A compromise on price would inevitably result in a compromise on quality,” he said.

The cost is also not the only headache: to get one million modules by the time the 2023 election swings around, Pakistan will need to produce 3,000 modules a day, and that too non-stop, Majeed revealed.

Will there be any other costs?

The cost of the modules accounts for the major chunk of the expected expense, but yes — there will be more to worry about.

To operate the EVMs on election day, Pakistan will need to train 300,000 to 500,000 people. The cost for this will come to about Rs1 billion, assuming the government incurs a cost of about Rs2,000 per head on training.

There will also be a need for technical support, in case a machine malfunctions on polling day.

Providing tech support in all 130 districts of Pakistan will carry a price tag of Rs250-500 million, approximately, assuming about 10 mobile units with 3 engineers each are assigned to each district. Going by this estimate, the ECP will need 1,300 mobile units and 4,000 engineers/technicians to provide tech support. The cost of operating each mobile unit is estimated to be Rs350,000-400,000 (including logistics, fuel, TA/DA, stipend costs and assuming the vehicles will be leased and not purchased).

Once these machines are used on election day, they will also need to be stored securely for five years till the next polls. This will require at least 12-24 large warehouses. The cost for this will ring up to Rs240 to 500 million per year, going by an estimate of Rs20 million per warehouse (minimal figure — this includes land purchase cost, warehouse constructions costs, HVAC and other equipment needed to keep the internal environment dust free).

And then of course, there will be the election day cost of Rs10-15 billion. This data is extrapolated:

- The 2013 election cost: Rs4 billion

- The 2018 election cost: Rs21 billion (major chunk went to security)

Going by these numbers, the main breakdown of costs will be:

- Logistics (of transporting 1 million modules from 12/24 warehouses to all polling stations).

- Batteries to run the machines (will be discarded after elections, can’t be stored due to limited life).

- Voter education (this is a major element — the ECP will need to run national campaigns to familiarise the population with the new equipment).

- Compensation for 300,000 – 500,000 polling staff.

- Close out costs (secure withdrawal of voting machines after election; having them stored).

Adding it all up, the total comes to about Rs70bn.

How many countries are using EVMs?

Majeed argues that as per the EU Parliamentary Research Services 2018, there are 195 countries in the world, of which 167 are self-described democracies. From among these, only eight countries are using electronic voting during polls, while nine countries have abandoned the idea.

[ad_2]